The great bells of Bow: a visit to the tower of St Mary-le-Bow

- London On The Ground

- Nov 1, 2025

- 6 min read

Bells, bell ringers and panoramas of a City of London landmark.

St Mary-le-Bow is one of Sir Christopher Wren’s most celebrated City of London churches. Its 248ft spire on Cheapside completes the most ‘Wren-like’ of the City churches he created after the Great Fire of London of 1666. It remains a landmark in the 21st century City.

However, St Mary-le-Bow is probably most famous for its bells, whose history long predates the Wren church.

Walks available for booking

For a schedule of forthcoming London On The Ground guided walks and tours, please click here.

The first church on the site was built in 1080. The original crypt remains today, a very rare example of Norman architecture in central London. For the best part of a millennium, St Mary-le-Bow has occupied a prominent position on Cheapside, the City’s main commercial thoroughfare, a route for royal processions and the site of medieval jousting tournaments.

The church’s importance was further underlined through being the London headquarters of the Archbishop of Canterbury and the venue for the Court of Arches (an ecclesiastical law court).

For centuries there was probably only one bell in the church tower and from at least as early as 1334, it rang the curfew at the end of the working day. This signalled that apprentices should be back in their masters’ homes, that the City gates should be closed and that fires should be covered (curfew derives from the Old French “couvre-feu”).

By tradition, only those born within earshot of Bow Bells (the bells of St Mary-le-Bow) are true Cockneys. The origin of this tradition and the derivation of the term Cockney are lost in the mists of time. However, I like the explanation that the Old English term “Cocken-ei” or “Cockernay”, meaning the egg of a cockerel, was used to describe Londoners by visitors to the City. Basically, Londoners are a bunch of cock’s eggs!

The fame of Bow Bells also owes much to the legend of Dick Whittington, who is said to have returned to London after hearing the bells of St Mary-le-Bow call out to him when he was on Highgate Hill while running away to his hometown.

Adding further to the myth of the bells of this prominent church is the reference to the “Great Bell of Bow” in the nursery rhyme Oranges and Lemons (see my post Oranges and lemons: bells and churches, with a moral to the story).

The weight of all this history, myth and heritage sat lightly with Annemarie and me when we met Simon Meyer, Tower Secretary, on a fine early October evening recently. We were excited to have a rare chance to climb the tower of St Mary-le-Bow in order to enjoy the views and to see and hear its bells.

We entered the base of the tower via one of its two large external doors and then went through a small door in its southeast corner to ascend the spiral staircase.

After an initial stop in the bellringing chamber, we continued up to look at the 12 bells, cast in 1956 to replace those destroyed in World War II. The bells are suspended from a wooden frame and arranged around the tenor, the largest of the dozen.

This is the Great Bell of Bow. With a diameter of 61¼ inches and weighing almost 42 cwt (2,135 kg), it is tuned to the note of C. The smallest bell, the treble, has a diameter of 27¾ inches, weighs 5 cwt (285 kg) and is tuned to G.

Each of the bells has a name and an inscription from the Bible. The first letters of each of the inscriptions spell out “D WHITTINGTON”.

The first bells in Wren’s post-Great Fire St Mary-le-Bow were a ring of 10, installed in 1677. They were recast in 1762 and extended to 12 in 1881, but by 1926 they had deteriorated to such an extent that they were considered no longer ringable.

It took until 1933 for the bells to be recast, paid for by H Gordon Selfridge, the US retail entrepreneur who founded Selfridges on Oxford Street (although whether he actually paid is disputed).

Shortly after the bells' rededication by the Archbishop of Canterbury, the BBC World Service made a recording of them for use on its radio programmes (some sources say the recording was made in 1926). Their sound became familiar to many in the occupied nations of Europe during World War II, who tuned in to BBC broadcasts whenever possible.

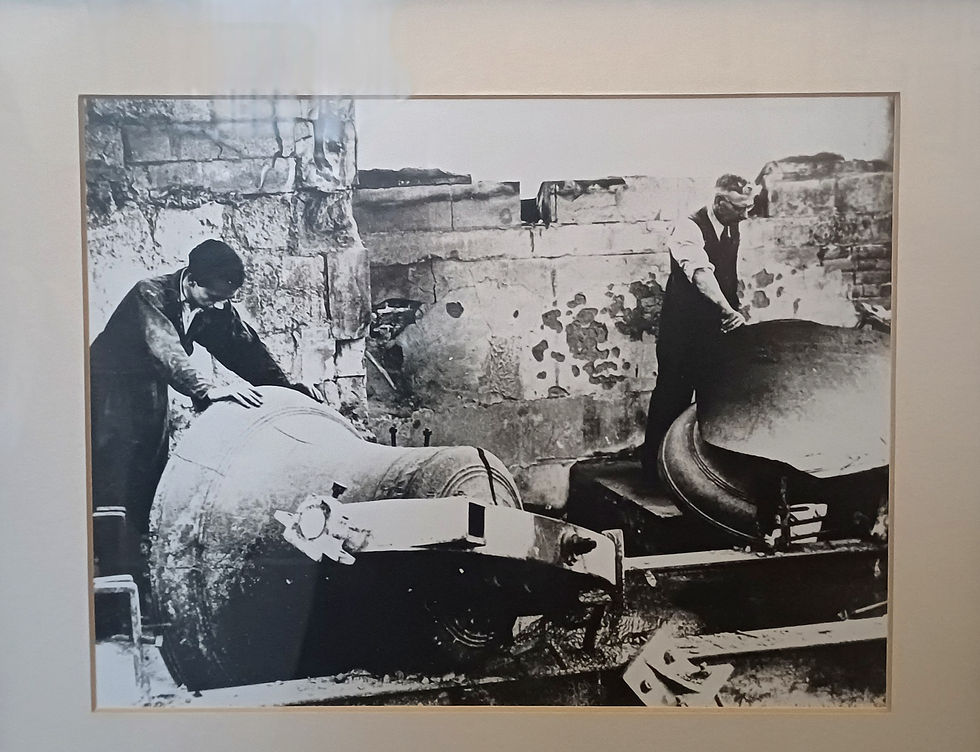

Sadly, the 1933 ring of 12 lasted less than eight years. On the night of 10 May 1941, the last night of the Blitz, the church was hit by incendiary bombs. All of the wood in the tower was burnt out, including the floors, the bell ringing chamber, the louvre window fittings and the frames on which the bells were hung. The bells crashed to the ground and were damaged beyond repair.

The new bells were cast by founders Mears & Stainbank at Whitechapel in 1956. They were not rung until December 1961, as repairs to the tower needed to be completed first.

However, the Lord Mayor of London at the time of the recasting in 1956, Cuthbert Ackroyd, was keen to hear the bells during his mayoralty. In the bellringing chamber today a photograph shows him striking the bells with a large mallet while they were still in the foundry.

The form of bell ringing that is prevalent in English church towers is known as change ringing, which originated in the early 17th century. It consists of sequences of successive rounds where the order of ringing of each bell varies around a descending scale in complex patterns.

In the City of London the principal change ringing organisation is the Ancient Society of College Youths, founded in 1637. Originally a recreational activity for gentlemen, change ringers were typically at that time young aristocrats and students (usually the sons of the upper classes). Membership later evolved to include men from a greater range of backgrounds and, from 1998, women.

The longest sequence of changes, a peal, consists of 5,000 or more rounds and takes around three and a half hours. The changes, or touches, have mysterious names, such as Stedman Cinques, Kent Treble Bob Maximus and Spliced Surprise Maximus.

Boards on the walls of the bell ringing chamber in St Mary-le-Bow record details of peals of the past, naming the members of the band, the peal they rang, the date and how long it took.

The longest sequence recorded in the chamber is a peal of Stedman Cinques of 11,111 changes on 8 May 1998, lasting just over eight hours non-stop! Simon told me that this meant no toilet breaks. “It’s OK, you just dehydrate”, he said.

Before witnessing a practice ringing session, Simon took us to the top of the tower to enjoy the fabulous views across London.

Click on any image to enlarge

He even agreed to take us to the second level of the steeple, a circular platform surrounded by flying buttresses, for still better views!

Click on any image to enlarge

Back in the bell ringing chamber, I was very impressed by the band of ringers in St Mary-le-Bow. With no ‘sheet music’ or other visual cues to remind them of the sequences, they rang out changes from memory with what seemed to me perfect timing over several minutes.

When you consider that the order in which the bells are rung is never the same from one round to the next and that there is a delay between pulling on the rope and hearing the bell ring, this is extremely impressive! These are very experienced ringers, the elite of their art!

We heard a Bristol Surprise Maximus and a Zanussi Surprise Maximus before thanking Simon and the team and leaving them to their art.

As we left, the sound of Bow Bells provided the perfect soundtrack to accompany our fresh memories of the magnificent views from the church tower.

Click on any image to enlarge

Walks available for booking

For a schedule of forthcoming London On The Ground guided walks and tours, please click here.

This was one of the best evenings of my life and has inspired me to take up bell-ringing!