Sadler’s Wells Theatre is a museum of its own history

- London On The Ground

- Nov 22

- 8 min read

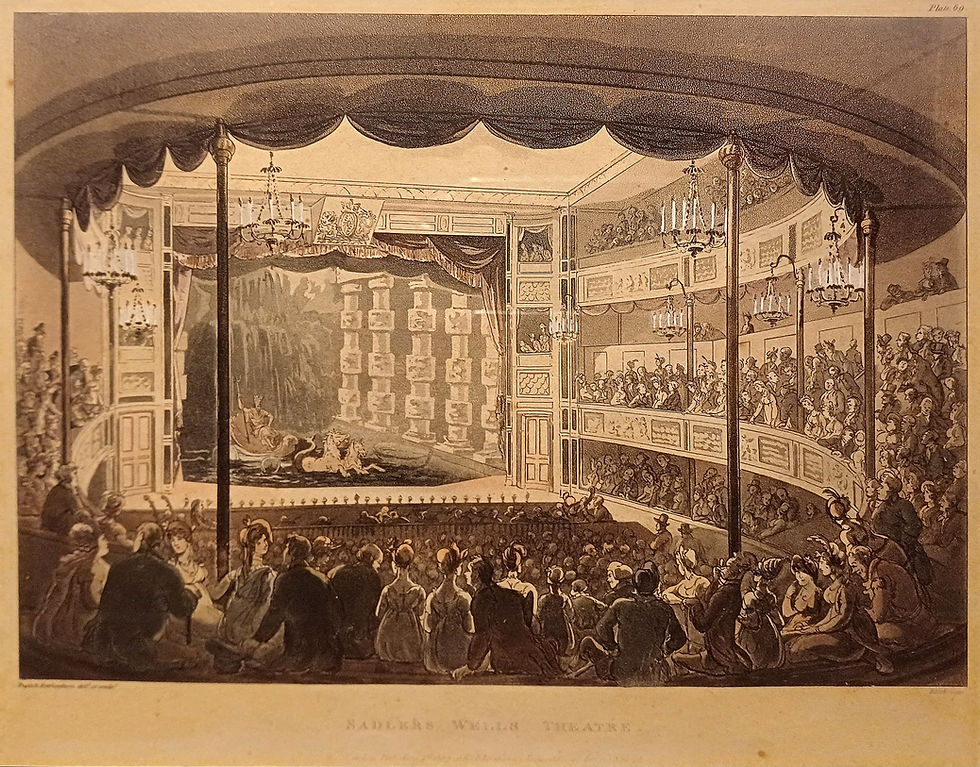

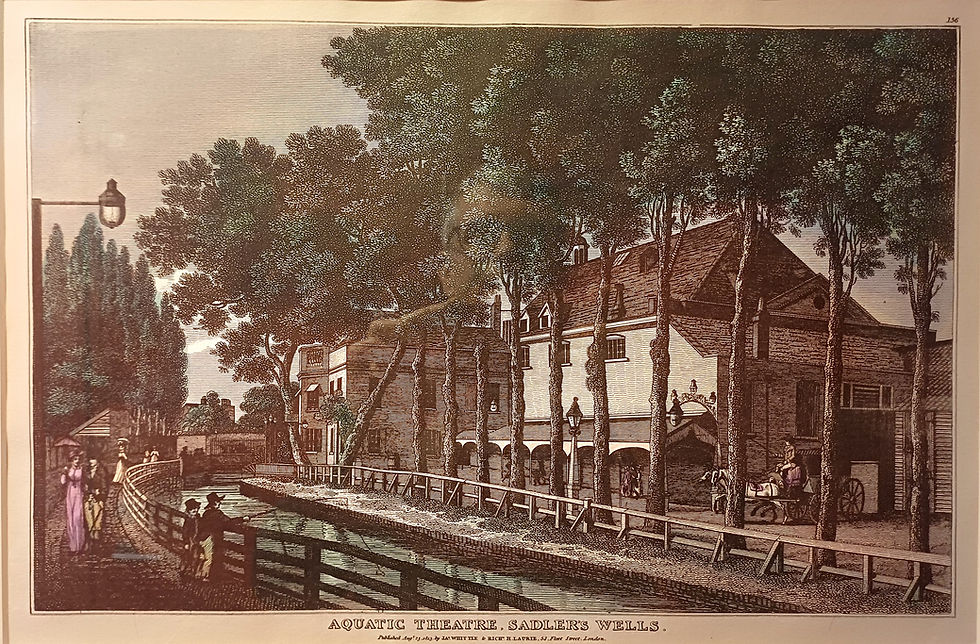

Over more than 300 years it has staged everything from aquatic shows and Shakespeare to pantomime and ballet.

Today Sadler’s Wells is London’s leading venue for dance, both classical ballet and contemporary dance.

The corridors of its 1,500 seat main auditorium and 182 seat Lillian Baylis Studio serve as a museum to its long and varied history.

All the artworks, engravings and sculptures in this post are London On The Ground photographs of items displayed at the Theatre and Studio.

Walks available for booking

For a schedule of forthcoming London On The Ground guided walks and tours, please click here.

The current building on Roseberry Avenue, just down the road from Angel tube station, was completed in 1998, but the story of Sadler’s Wells stretches back over more than 340 years.

In that time, the theatre has been rebuilt five times and has staged a wide variety of entertainments including music, tumbling, opera, dancing, Shakespeare, pantomime, aquatic shows, roller skating, performing animals, boxing and wrestling.

Sadler’s Wells was established in 1683 as a ‘Musick House’ by an entrepreneur named Sadler, whose first name is variously recorded as Richard, Dick, or Edward.

He discovered a medieval well under the garden and started to promote the healing properties of the waters. Patrons could take the waters, while also enjoying the music.

Sadler claimed that his well water was Effective against "dropsy, jaundice, scurvy, green sickness and other distempers to which females are liable—ulcers, fits of the mother, virgin's fever and hypochondriacal distemper."

A number of other spas opened in the Clerkenwell and Islington area, which was still largely rural in the late 17th century. This attracted competition for Sadler’s Wells, whose well dried up in the 1700s, so its entertainments moved downmarket in order to attract customers. By 1711, Sadler's Wells characterised as "a nursery of debauchery."

There were a number of revivals and further descents in its fortunes and in its artistic merits. The theatre was rebuilt in 1765, 1802, 1879, 1931 and 1998.

Sadler’s Wells is a very contemporary venue, but it is also rightly proud of its long history. In the corridors of the main theatre and the Lillian Baylis Studio there are many pictures, sculptures and other artefacts displaying its heritage (there is also an excellent café in the Lillian Baylis Studio, worth visiting even if you are not going to a show).

I recently visited Sadler’s Wells on a tour organised by the Islington Society and took photographs of many of these items.

My first group of photographs below are of images showing the theatre at various times in its history.

In Evening by William Hogarth, one of a satirical 1738 series depicting different times of day, the entrance to Sadler’s Wells is on the left, the Sir Hugh Myddleton inn is on the right.

On the evening of 15 October 1807, someone shouted a false alarm of fire during a packed performance. This led to the deaths of 18 people and a number of injuries to others present.

By this time Sadler's Wells had been rebuilt again, this time with a massive water tank under the stage. Filled from the New River, which passed outside the theatre, the tank was used for great aquatic shows, including re-enactments of famous naval battles.

These water shows and the tragedy of the false fire alarm added to the theatre's fame, but coincided with a period of low artistic merit and rowdy and drunken audiences at Sadler's Wells.

The fourth theatre was built in 1879, by which time the whole area was urbanised. In an attempt to capture a broad market, it developed a varied programme, including Shakespeare plays, roller skating rink, prize fights, music hall and even early cinema. However, in 1916 it closed due to World War I and never re-opened.

The vision and determination of Lillian Baylis (see below) saved the venue in the form of the fifth Sadler’s Wells in 1931.

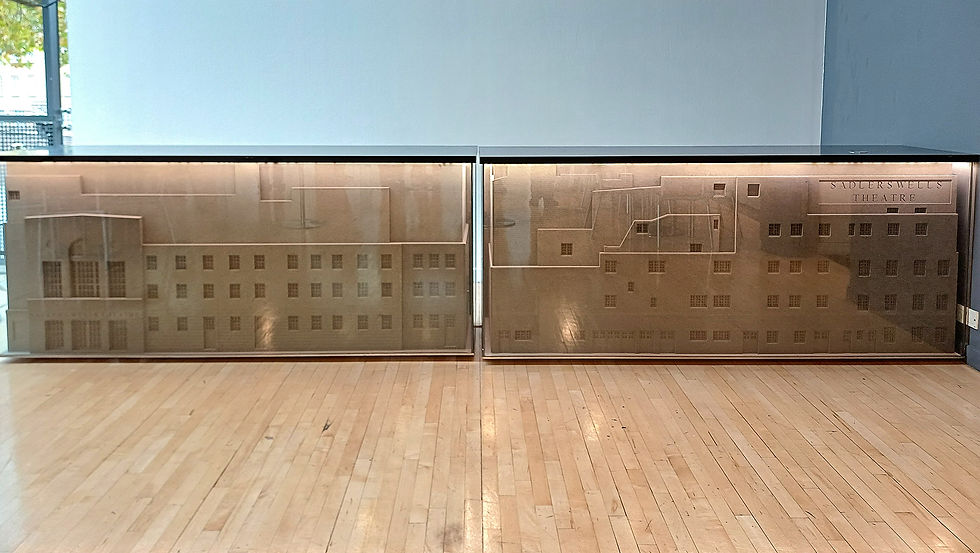

It opened with a production of Shakespeare's Twelfth Night on 6 January. Many traces of that theatre remain visible today.

Through a window in the reception area of the Lillian Baylis Studio, you can see a stone relief, The Water Carriers, carved by Joseph Hermon Cawthra in 1931. It depicts women drawing water from the well and was placed above the main entrance of the 1931 theatre.

Cawthra also carved stylised masks of Comedy and Tragedy, which were placed over the main entrance, either side of The Water Carriers. These two stone masks are now in a corridor off the foyer of the main theatre.

Click on any image to enlarge.

The front and rear elevations of the 1931 theatre are reproduced in reliefs displayed on a first floor bar in the main theatre.

The opening production on 6 January 1931 (Twelfth Night) featured John Gielgud as Malvolio and Ralph Richardson as Sir Toby Belch. Gielgud later said, “we all detested Sadler's Wells...[it] looked like a denuded wedding cake, and the acoustics were dreadful”.

Neverthless, other young actors who would become giants of stage and film - such as Laurence Olivier, Peggy Ashcroft and Alec Guiness - also appeared at Sadler's Wells in the 1930s.

The next group of photographs show people with strong associations with Sadler’s Wells from the 19th to the 21st centuries.

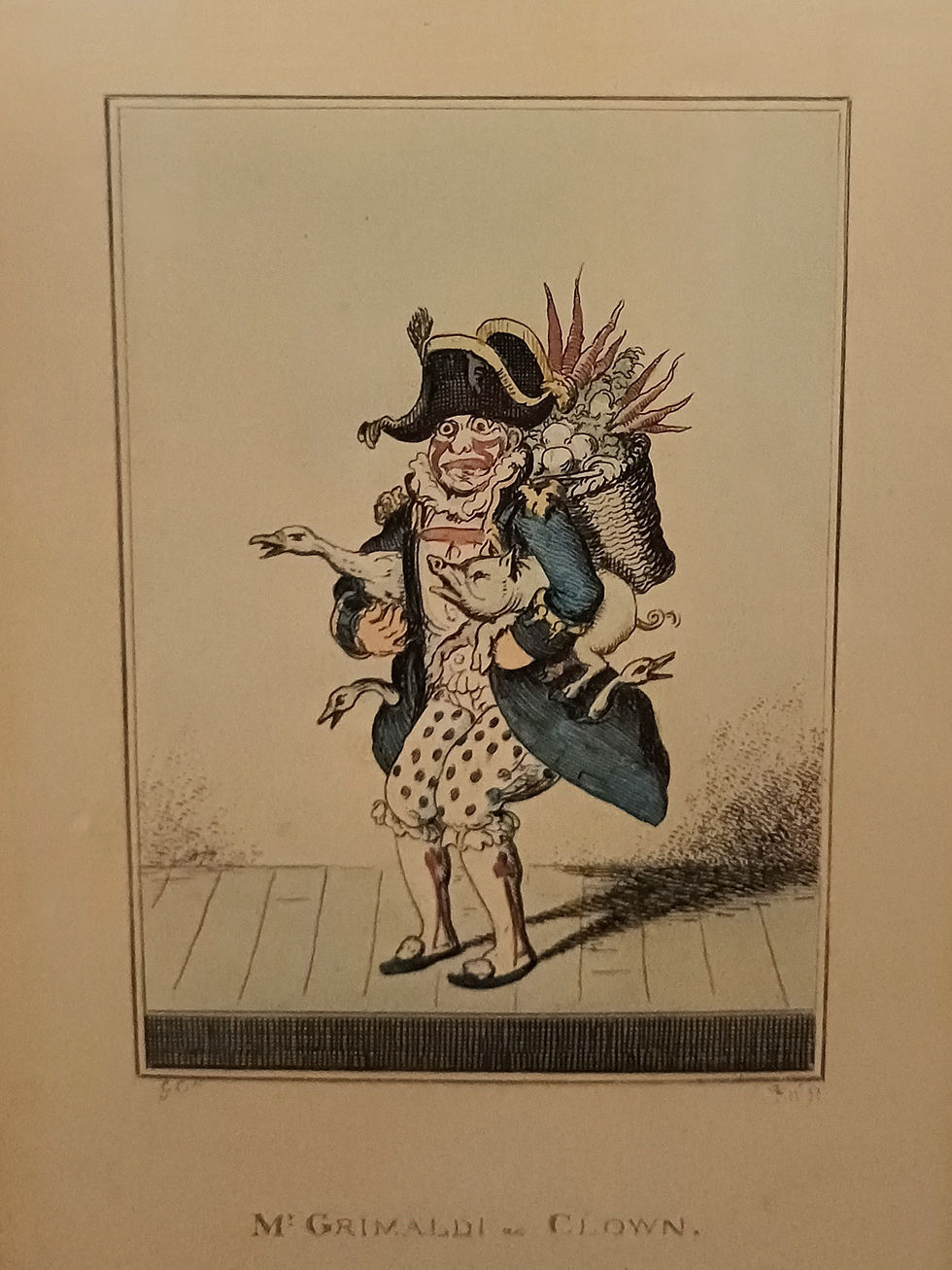

Joesph Gimaldi (1778-1837) was the greatest comic actor and entertainer of his time. He helped to popularise pantomime with his Clown character known as Joey and devised the style of costume and make-up still used by clowns today. He performed at Sadler’s Wells from the age of two until 1820 and also appeared regularly at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, and the Covent Garden Theatre.

Edmund Kean was a celebrated Shakespearean actor in the early 19th century, establishing himself at the Theatre Royal Drury Lane and performing in America on two visits. He first appeared at Sadler’s Wells as a teenager in 1801.

Samuel Phelps (1804-1878) managed Sadler’s Wells from 1844 to 1862, also starring in many productions, during the theatre’s revival as an important venue for Shakespeare’s plays.

Lillian Baylis (1874-1937), mentioned earlier, was one of the most significant theatre managers in London in the 20th century.

After turning the Old Vic from a downmarket music hall venue to a theatre for ‘legitimate’ drama, including Shakespeare, she rescued Sadler’s Wells from obsolescence and closure in 1925.

Alongside the Old Vic, she managed the rebuilt Sadler’s Wells from its opening in 1931 until her death in 1937, re-establishing its reputation for Shakespeare and, in particular, opera and ballet.

The English National Opera, the Royal Ballet and the National Theatre all emerged from the companies that Lillian Baylis managed at Sadler’s Wells and the Old Vic.

Her portrait, by Ethel Gabain, hangs -appropriately - in the entrance to the Lillian Baylis Studio.

Next to the portrait is a letter written by Lillian Baylis to the artist (addressing her by her married name of Mrs Copley). She notes that all the staff like the frock the artist suggested she wear for the sitting.

Ninette de Valois (1898-2001), regarded as one of the most important influences in 20th century ballet, has been called the godmother of English and Irish Ballet.

She was engaged by Lillian Baylis, originally at the Old Vic in the 1920s, and then founded the Sadler’s Wells Ballet Company and the Sadler’s Wells Ballet School. Under her leadership, these two organisations evolved into the Royal Ballet Company and the Royal Ballet School.

De Valois worked closely with choreographer Frederick Ashton (1904-1988) from 1931 at Sadler’s Wells, Covent Garden and at the Royal Ballet. He succeeded her as Director of the Royal Ballet when she retired in 1963.

Alicia Markova (1910-2004) was the first British dancer to be a prima ballerina (the principal dancer of a ballet company). She was with the Vic-Wells Ballet and Sadler’s Wells Ballet Company from 1932 to 1935.

Anton Dolin (1904-1983) was a principal with the Vic-Wells Ballet in the 1930s, dancing with Alicia Markova. Together they formed the Markova-Dolin Ballet and London Festival Ballet (now English National Ballet).

Margot Fonteyn (1919-1991) was prima ballerina at the Sadler’s Wells Ballet Company from the 1930s (after Alicia Markova). She continued with the company after it moved to the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden and when it became the Royal Ballet. She retired from dancing in 1979.

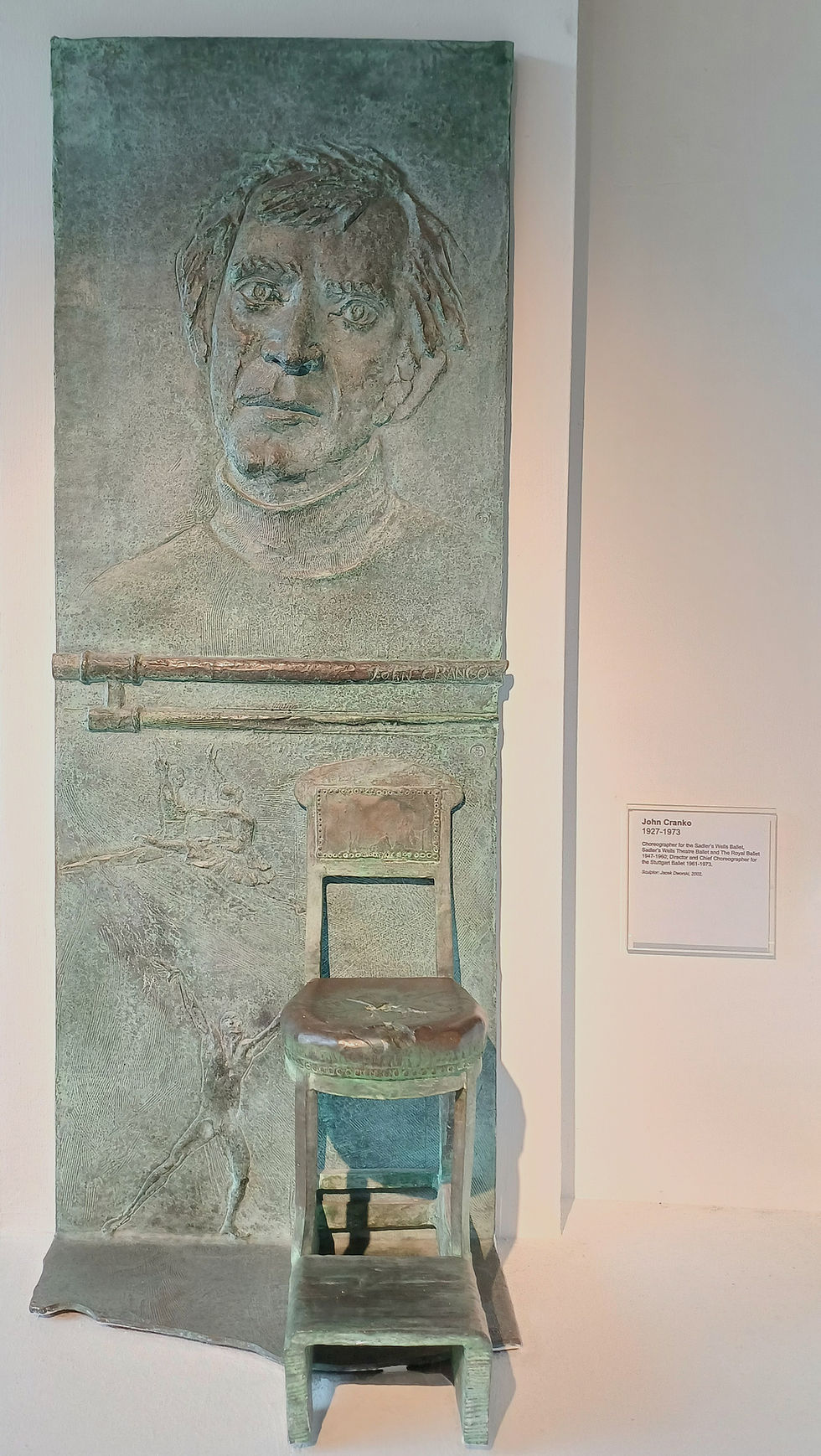

John Cranko (1927-1973) was choreographer for the Sadler’s Wells Ballet, Sadler’s Wells Theatre Ballet and the Royal Ballet 1947-1960.

The six busts below, in the entrance to the Lillian Baylis Studio, are all of dancers with string links to Sadler's Wells. They are Peter Darrell (1929-1987), Michael Somes (1917-1994), Margot Fonteyn (see above), Peter Wright (b. 1926), Peggy van Praagh (1910-1990) and Leslie Edwards 1916-2001).

Ian Albery (b. 1936) was chief executive of Sadler’s Wells Theatre from 1994 to 2002 and oversaw the design and construction of the existing building (the sixth theatre on the site, opened in 1998).

Dancer Jonathan Byrne Ollivier (1977-2015) was on his way to give his final performance in Matthew Bourne's The Car Man at Sadler’s Wells in August 2015. Tragically, he was killed when a minicab hit his motorbike on Farringdon Road. In January 2016 Sadler’s Wells staged a special tribute to him, hosted by Sir Matthew Bourne and featuring extracts from a number of ballets.

Today’s Sadler’s Wells, completed in 1998, has fabric from its two immediate predecessor buildings. It still contains the skeleton of the 1931 theatre, which also includes bricks from the 1879 building. Its construction was supported by the National Lottery through the Arts Council.

Its glass-fronted foyer provides a bright, airy space which connects the theatre to the world outside.

According to an article on the Sadler’s Wells website, this “captures Lilian Baylis’ belief that theatre should embrace everyone”.

In 2000, the Islington Society presented the still new Sadler’s Wells Theatre with the Geoffrey Gribble Memorial Conservation Award.

The award recognised the best recent building in Islington and was named after Geoffrey Gribble, the borough’s Conservation Officer for many years until his death in 1988.

Although the original well has not been used for many a long year, Sadler’s Wells still uses water from the aquifer beneath the building in its air conditioning system and in the toilets and wash basins.

What’s more - the greatest example of the way Sadler's Wells preserves its history - the original well can still be seen. Down a corridor off the right hand side of the foyer, there is a circle of thick glass in the floor.

Look down through the glass and you can see the well several metres below.

Walks available for booking

For a schedule of forthcoming London On The Ground guided walks and tours, please click here.

Comments