Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle: “Mad Madge”, or a woman ahead of her time

- London On The Ground

- 2 days ago

- 7 min read

The 17th century writer, poet, philosopher, scientist and playwright questioned the role of women and divided opinion.

Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle (1623-1673), was a prolific writer of non-fiction and fiction, essays, poems and plays. Her aim was uniqueness in dress, thoughts and behaviour. Unusually for a woman at the time, her works were published, and under her own name. She designed her own clothes, was open about seeking fame and was quite a celebrity in London after the Restoration.

Source of the image of Margaret Cavendish above: Wikipedia, public domain.

Walks available for booking

For a schedule of forthcoming London On The Ground guided walks and tours, please click here.

With her utopian romance The Blazing World, she was a pioneer of the science fiction genre, while her theory of atomism also made her a pioneer in natural philosophy (science). Her themes also included philosophy, manners, emotions, gender and women’s education. Most of her interests - and writing itself - were generally considered to be in the male domain and not suitable pursuits for a woman in the 17th century.

In 1667 she was the first woman to attend a meeting of the Royal Society, a scientific body founded just seven years earlier. She is also regarded as an early critic of testing on animals.

Born to a wealthy family in Colchester in 1623, Margaret was the youngest of eight children of Sir Thomas Lucas and Elizabeth Leighton (she had four sisters and three brothers). She had no formal education, but the house had libraries and tutors and she began putting her ideas into writing from an early age. She also started to design her own clothes as a child. When her father died, Margaret’s mother ran her household with almost no male help.

During the English Civil War, when Charles I moved his court to Oxford, the 20 year old Margaret took a position as a lady-in-waiting to the Queen, Henrietta Maria. She had been inspired by the Queen leading an army under the adopted title "Her She-Majesty, Generalissima".

Margaret was shy and bashful among strangers, to the extent that she was regarded a fool by some in the Queen’s household (but she preferred that to being seen as wanton or ride). Nevertheless, in 1644, she accompanied Henrietta Maria into exile at the court of Louis XIV in Paris.

While in France she met William Cavendish, a Royalist military commander and one of the greatest horsemen of the age, who was Marquess of Newcastle and also now in exile.

In spite of a 30 year age gap and disapproval from the queen and their friends, they married in 1645. He found her bashfulness endearing and she was attracted by qualities she described as his courage, justice, quick-wittedness, noble nature and sweet disposition.

William had previously been known as a womaniser, but became a devoted husband and was very supportive of her literary endeavours. He was the only man Margaret ever loved (apart from Julius Caesar, Ovid and Shakespeare, with whom - she wrote - she was in love as a girl). The marriage did not produce any offspring, but William had five surviving children from his first wife.

During the period of the interregnum, William was regarded by the Cromwell regime as a traitor and so he could not return to England. In 1651 Margaret returned temporarily, with William’s brother Sir Charles Cavendish, in an unsuccessful attempt to derive some revenue from her husband’s properties. William had homes at Welbeck Abbey in Nottinghamsire, at Bolsover Castle, Derbyshire, and at Newcastle House in Clerkenwell Close, which was then on the outskirts of London.

Following the publication of her first book, Poems and Fancies, Margaret rejoined her husband after 18 months in England. On the Continent the couple mixed with philosophers and scientists, helping her to form and explore the ideas she developed in her writing.

Margaret and William returned to live in England after the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660. William was elevated by Charles II from Marquess to Duke of Newcastle in 1665. After recovering Newcastle House in Clerkenwell, which had been sold during the interregnum, the couple lived there for the rest of their lives.

When she attended a meeting of the Royal Society in 1667, its all-male membership included intellectuals and great figures of science such as Isaac Newton, Robert Boyle, Robert Hooke and Christopher Wren. She witnessed demonstrations of “colours, loadstones, microscopes and of liquors” and Boyle’s air pump experiments.

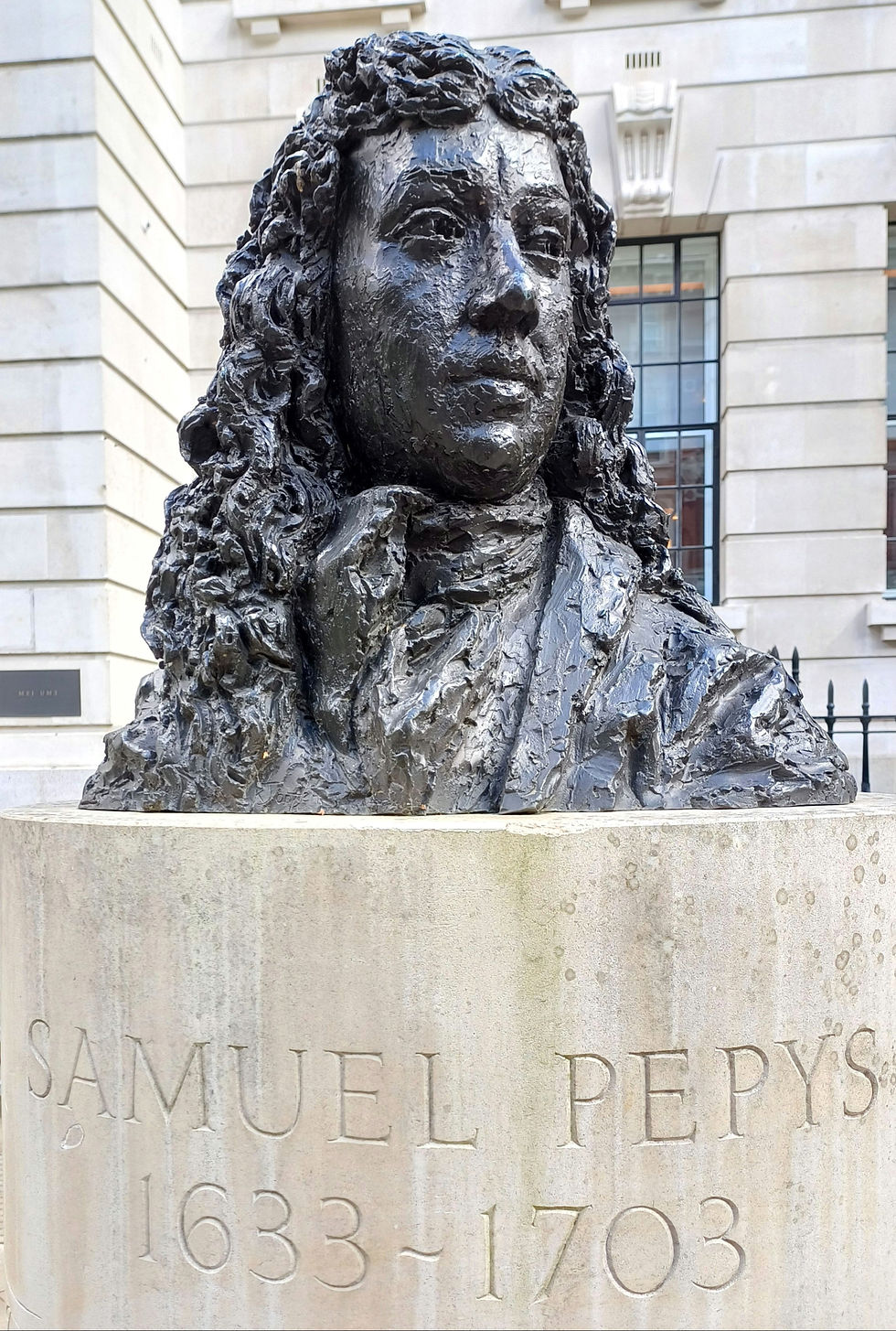

It is not clear if Margaret’s nickname ‘Mad Madge’ arose during her lifetime or later. However, Samuel Pepys, the great London diarist and also a Royal Society member, described her as a “mad, conceited, ridiculous woman”.

Samuel Pepys was critical, but, it seems, also captivated:

“…all the town-talk is now-a-days of her extravagancies, with her velvetcap, her hair about her ears; many black patches, because of pimples about her mouth; naked-necked, without any thing about it, and a black just-au-corps [a knee-length coat mainly worn by aristocratic men]. She seemed to me a very comely woman: but I hope to see more of her on Mayday.”

Her celebrity attracted crowds when she rode in her carriage around London. As a result, Pepys was unable to get close enough to see her on Mayday in Hyde Park and he also failed to see her in Clerkenwell 10 days later when crowds of children chased after her coach. When he finally saw Margaret Cavendish at the Royal Society on 30 May, Pepys was dismissive:

“The Duchesse hath been a good, comely woman; but her dress so antick [old], and her deportment so ordinary, that I do not like her at all, nor did I hear her say any thing that was worth hearing…”

Another Royal Society member, John Evelyn (also a great diarist) called her a “mighty pretender to learning, poetry and philosophy”. This could be interpreted both positively and negatively, but Evelyn visited the Duke and Duchess of Newcastle in Clerkenwell twice in 1667 and “sat discoursing with her”. He was “much pleased with her extraordinary fancifull habit, garb, & discourse”.

Evelyn’s wife, Mary, was less impressed, describing Margaret as “obscene”. The Duchess is reported to have attended the premiere of a play, written by her husband, with exposed breasts and red-painted nipples. This was certainly a unique form of dress, but it caused a scandal. It also ran contrary to her shyness, an example of the contradictions in her character than ran through her life.

Others saw her more positively.

Bathusa Makin, known as England’s most learned lady and who advocated that women and girls had the same right to education as men, wrote:

"The present Dutchess of New-Castle, by her own Genius, rather than any timely Instruction, over-tops many grave Gown-Men."

However, her critics outweighed her admirers. Henry More, a philosopher, theologian and poet, wrote that Margaret “may be secure from anyone giving her the trouble of a reply”. He was right. Her attempts - in the form of passages added to her books - to stimulate discussion of the ideas in her work largely failed during her lifetime.

With thoughts of her legacy, Margaret donated special folio editions of her books to all the college libraries at Oxford and Cambridge Universities, a noteworthy act at a time when women were not admitted to universities. Some colleges thanked her, but, in most cases, the books were stored without acknowledgement.

By the early 20th century, Margaret Cavendish and her work were largely forgotten. The writer Virginia Woolf has been credited with rediscovering her in a 1925 essay, but even Woolf’s views on Cavendish were mixed.

Woolf considered her philosophies to be “futile, and her plays intolerable, and her verses mainly dull”. Nevertheless, she also praised the Duchess’s “vein of authentic fire” and the “lure of her erratic and lovable personality”.

Woolf was attracted by Cavendish’s contradictions: “There is something noble and Quixotic and high-spirited, as well as crack-brained and bird-witted, about her. Her simplicity is so open; her intelligence so active.”

Even Cavendish herself seemed unsure of her own literary merits. She felt that she did not write elegantly, that she struggled to create rhymes and that she expected criticism that her work was not useful.

However, her aims with her writing were to communicate ideas and to pass her time in a better way than others. She considered writing a better use of time than gossip, a more common female activity. She also sought fame and invited praise through her writing.

Cavendish was aware that, as a female writer, her work might be ridiculed. She asked that it be judged by reason, not prejudice. Yet, writing that she liked her own poetry, she said she wrote it without thinking of how it would be received by critics.

She also wrote about how she argued with Reason, who told her to stop writing as it was a waste of time and would not be well received and there were already too many books. Dismissing these thoughts, she had her book published, but then later regretted this and was ashamed of her writing.

In spite of these doubts, she was prolific. She produced around 22 books in her lifetime, including revised editions of some of them. Always coming up with new ideas, she had a footman sleep on a pull-out bed in a closet of her bedroom, ready to record her nocturnal musings as soon as they struck her.

Margaret Cavendish died at the age of 50 in December 1673, three years before her husband. They were both buried in Westminster Abbey, where there is a marble monument to them. It was carved by Grinling Gibbons, the greatest sculptor of his age.

The “Mad Madge” epithet probably says more about historical attitudes towards women regarded as unconventional than it says about the state of Margaret’s mental health.

Margaret Cavendish may have fallen short in stimulating a response from others on her writings. However, she certainly achieved her aims of uniqueness and fame.

Walks available for booking

For a schedule of forthcoming London On The Ground guided walks and tours, please click here.

Brilliant!